For Education Leaders

Get proven strategies and expert analysis from the host of the Learning Can't Wait podcast, delivered straight to your inbox.

Virtual Resource Rooms

Compliant IEP Support Without Staffing Headaches

- Certified SPED teachers for every goal

- Seamless schedule integration & progress dashboards

- Real-time data for reviews & compliance

IEP Explained: Your Guide to Special Education Plans (IDEA)

Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) are a crucially important concept in the education system as they provide opportunities for special education instruction and accommodation for students with specific disabilities. Governed by the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA), these legally binding documents aim to offer free appropriate public education (FEPA) to children with disabilities that allow them to thrive academically, reach their full potential at school, and get prepared for life after graduation, whether in post-secondary education or career. Implementation of effective IEPs often requires access to qualified specialists, including virtual special education teachers who can provide additional support when local staffing resources are limited.

IEPs are regulated by strict rules and requirements that school administrators, teachers, and other education professionals need to be familiar with in order to refer children in need of specialized assistance and deliver special education in the most effective manner. Developing and implementing an IEP is a complex process that involves multiple parties, and schools need to know how to lead and manage the process for smooth procedures and optimal results for students and their families. When challenges arise, families may benefit from working with special education advocates to ensure their child's needs are properly addressed.

Does your district need special education teachers for successful IEPs? Fullmind staffing services provide districts with state-certified, K-12 special ed teachers, while Fullmind supplemental instruction services offer Certified Students with Disabilities Teachers for virtual full-time or part-time resource room instruction.

What an IEP Is

An Individualized Education Program (IEP) is a legal document that outlines the special education instruction, services, and support that a student with specific types of disabilities needs to receive at a public school in order to reach their full academic potential and succeed at school. IEPs are available to PreK-12 students within one or more of 13 disability categories that prevent them from thriving academically when following standard education curriculum, instruction, and process. Many schools rely on Title 1 special education funding to help provide these essential services and supports.

The Individualized Education Program was first introduced in the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) of 1975, which aimed to ensure that all children with disabilities have access to free appropriate public education (FEPA) within the US education system. Currently, IEPs are covered by the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA), which replaced EHA in 1990. The purpose of IDEA is to provide FEPA that emphasizes special education and related services in a way that meets the unique needs of children with disabilities and prepares them for further education, employment, and independent living. IDEA also defines the 13 disability categories that allow a student to qualify for an IEP.

At the federal level, IEPs are governed by the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) of the U.S. Department of Education. In addition, each state has a dedicated agency under the Department of Education that is responsible for the implementation of Individualized Education Programs at the state level, including adaptations for online learning for students with disabilities.

It’s important to note that IEPs need to be designed as a collaborative effort between a number of relevant stakeholders in order to be effective and meet the specific needs of each student in the most appropriate manner. In specific, schools are required to involve parents in the IEP process.

Additionally, as the name suggests, IEPs have to be personalized - or individualized - to the unique needs of every child, taking into consideration both their weaknesses and their strengths to provide the best possible academic and emotional outcome.

What an IEP Must Contain

Each Individualized Education Plan needs to have a few components to be IDEA-compliant.

The required information includes:

- Current performance: Statement of the child’s present levels of academic achievement and functional performance including how the disability affects the child's involvement and progress in the general education curriculum. This information comes from evaluation results such as classroom assignments and tests, individual tests, and observations by parents, teachers, related service providers, and other school staff.

- Annual goals: Statement of measurable and reasonable annual academic and functional goals broken down into short-term objectives or benchmarks.

- Measuring progress: Description of how the student’s progress towards the set annual goals will be measured and when periodic progress reports will be provided to the parents and others involved.

- Special education and related services: List of the special education, related service, and supplementary aids to be provided to the child including modifications to the program or support for school personnel, such as training or teacher professional development, to equip them with the skills and knowledge to assist the student.

- Participation with nondisabled children: Explanation of the extent to which the child will not participate with nondisabled children in regular classes and extracurricular and nonacademic activities, if any.

- Participation in state and district-wide tests: Statement of necessary individual accommodations and modifications in the administration of state and district tests including alternative testing methods if standard tests are not appropriate for the child.

- Dates and places: Expected date for the beginning of services well as anticipated frequency, location, and duration of services.

- Transition services needs: Statement of the courses the child needs to take to reach their post-school goals beginning when the child is age 14 (or younger, if appropriate). Statement of the transitions services that are needed to help prepare the student for leaving school beginning when the child is age 16.

To cover all this detailed information and offer efficient support to students with disabilities, an IEP has to be prepared in cooperation between professionals from the school and the parents of the student.

Who Gets an IEP

There are a number of criteria that a student needs to meet in order to get an IEP.

First of all, IEPs are available to PreK-12 students enrolled in the public education system which includes public school and charter schools. While most private schools have some kind of special education, they do not necessarily offer IEPs in the same way that public schools are legally obliged to provide.

Second, Individualized Education Programs are available to eligible children ages 3 and up. This covers ages from preschool to grade 12. Babies and toddlers with special needs can access specialized services through early intervention but not IEPs. Similarly, IEPs are not meant for tertiary education students who can benefit from other types of special education services at college and university.

Third, a child must have one or more of the 13 categories of qualifying disabilities under IDEA to be eligible for an IEP.

The 13 disability categories cover:

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Deaf-Blindness

- Deafness

- Hearing Impairment

- Speech or Language Impairment

- Visual Impairment including Blindness

- Traumatic Brain Injury

- Orthopedic Impairment

- Specific Learning Disability

- Emotional Disturbance

- Intellectual Disability

- Multiple Disabilities

Determining a child’s eligibility for special education and an Individualized Education Program under IDEA requires a few steps that involve a number of stakeholders.

IEP Process Explained in 10 Steps

IDEA specifies a 10-step process for special education that ensures that children in need of an IEP are properly identified and provided with the most appropriate plan to succeed academically in accordance with their specific situation. The process starts with identifying children who might be in need of special education, goes through confirming eligibility and preparing an IEP, and concludes with periodic reevaluations.

The 10 steps of the IEP process that public schools have to apply include:

- Need discovery: As a first step, the state needs to identify, locate, and evaluate all children with disabilities who might need special education and related services. This is done via the so-called Child Find activities. A child might be referred for evaluation by the Child Find system, the parents, the child’s teacher, or another school professional. Parental consent needs to be obtained before a child can be evaluated. The evaluation must happen within a reasonable time after the parents’ consent.

- Child Evaluation: A comprehensive evaluation must assess the child in all areas of the suspected disability. The evaluation results are used to decide if the child is eligible for special education and related services and determine the appropriate education program for the child. Parents who disagree with the results of the evaluation can take their child for an Independent Educational Evaluation (IEE), the cost of which has to be covered by the school system if this is requested by the parents.

- Eligibility Decision: Together, a team of qualified professionals and the parents look at the results of the child evaluation and decide whether the child is a child with a disability as defined by IDEA. Parents who disagree with the decision can ask for a hearing to challenge it.

- Finding a Child Eligible for Services: The IEP team needs to meet within 30 days of finding a child with a disability who is eligible for special education to write an Individualized Education Program for the child. Each IEP is unique and needs to reflect the specific requirements and needs of the student. This is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

- Scheduling an IEP Meeting: The school system needs to schedule and hold an IEP meeting to put together an IEP document. This necessitates the following steps:

- Contacting the participants including the child’s parents.

- Notifying parents early enough to give them an opportunity to attend.

- Schedule the meeting at a time and location convenient to the school and the parents.

- Telling the parents the purpose, time, and place of the IEP meeting.

- Informing the parents who will be attending the meeting.

- Letting the parents know that they can invite to the meeting people who have knowledge or special expertise about the child including private tutors, advocates, friends, and others.

- IEP Meeting and Writing the IEP: The identified IEP team meets to discuss the child’s needs and write an IEP. Parents need to give their consent before a student can start receiving special education and related services for the first time. In case the parents disagree with the IEP, they can share their concerns with the team and try to figure out an alternative solution. They can ask for mediation if the team is not able to find an agreeable solution. In the worst case scenario, parents can file a complaint with the state education agency and request a due process hearing.

- Provision of Services: Implementation of the IEP should start as soon as the parents’ consent has been granted and needs to be performed exactly as stipulated in the document. A copy of the IEP is distributed to the parents and each of the student’s teachers and service providers so that they know their exact responsibilities including necessary accommodations, modifications, and supports.

- Progress Measurement and Reporting to Parents: Student’s progress towards achieving the annual goals stated in the Program is measured and monitored as outlined in the IEP. Progress reports are regularly provided to the parents to inform them about their child’s progress and whether it is enough to reach the goals by the end of the year.

- IEP Review: The IEP is reviewed by the IEP team a minimum of once per year; more frequent reviews might be requested by the parents or the school. The IEP is revised and adjusted as needed. Parents get invited to the IEP review meetings to make suggestions and agree or disagree with the goals and the placement. Parents have multiple options, listed above, to deal with situations where they disagree with the IEP.

- Child Reevaluation: The child needs to undergo reevaluations triennially, at least, to find if they continue to be a child with a disability and what their current educational needs are. More frequent evaluations are available if the condition of the child requires them or if the parents or a teacher asks for a reevaluation.

The IEP process, as mandated by IDEA, is rather demanding, but it is a must in order to not simply comply with legal regulations but also ensure that the school provides appropriate instruction and other educational services to students with different needs and disabilities. The most important factors for the successful implementation of an Individualized Education Program are the involvement of all relevant players, including the child’s parents and the child themselves, when appropriate, and the continuous measurement of progress and changes to the Program to reflect the evolving needs of the student.

IEP Funding Sources

As an indispensable part of special education, IEPs are funded through a number of government and other sources. What matters the most is that an Individualized Education Program is free of charge for the student and the parents as all children must have access to appropriate education, regardless of the type and severity of their disability.

The main sources of IEP funding include:

- Federal funds: Under IDEA provisions, the federal government is required to cover 40% of the additional cost associated with special education for eligible students. Every year, the federal government sends dedicated special education grants to states which distribute them to school districts.

- State funding: Most states supplement the federal funding with state-specific special education grants to cover another portion of the IEP costs.

- District funds: School districts can access additional sources to cover funding gaps, such as general education grants, other grants to fund specialized programs, and some taxes.

- Medicaid: Medicaid can cover costs of medical-related services, such as speech therapy, mental health counseling, and others, for eligible students.

- Private funding: Schools and districts can apply for different private grants provided by foundations and organizations to fund specialized programs and initiatives.

Although the financial cost of special education and IEPs can be covered in different ways, special education remains generally underfunded across the US. The main reasons for the financial gap is that while the federal government is expected to cover 40% of the total cost, according to IDEA, in reality it’s been covering an average of 14.7% of the additional expenses associated with IEP implementations.

Further cuts might be on the way, which can have a major negative impact on the ability of public schools to provide relevant educational and related services to students with disabilities. In the future, schools and school districts might need to look for additional alternative sources of funding to offer IEPs, such as private grants and funds.

IEP Team and Support

Developing and implementing an Individualized Education Program is a complex, multi-layered process that requires the active participation and involvement of various stakeholders to make sure that the specific needs of the student are addressed in the most fitting manner. It’s important that an IEP team includes representatives of the school, the district and local education authorities, and the parents to create a comprehensive overview of the needs and requirements of the child and work out a plan that best meets these needs.

While the composition of the IEP team can vary, the must-have members required by law include:

- General education teacher(s): The law demands that at least one of the child’s general education teachers be present on the IEP team. These are the educators who know best the current state of the student, their strengths and weaknesses in the classroom and outside it, and how they are performing with regards to the general education curriculum.

- Special education teacher(s): The team must include a minimum of one special education teacher who is working or will be working with the child. This specialized educator can make specific suggestions on the most appropriate accommodations and modifications to instruction and teaching methods to help the child do well academically.

- School district/local education agency (LEA) representative: The role of the school district representative is to approve the school resources necessary for the IEP. They need to have expertise in special education.

- Evaluation expert: This could be the school psychologist or the special education teacher already available on the IEP team. They have to be able to interpret the results of the child’s evaluation, provide insights into the student’s academic, cognitive, and behavioral needs, and offer recommendations on modifications and support.

- Parents/guardians: By law, the parents or the legal guardians of the child need to be present on the IEP team as they have the right to a say in their child’s education. In addition, they have the most in-depth knowledge and understanding of the student’s needs, strengths, weaknesses, struggles, and potentials. Moreover, they have the right to advocate for their child’s rights. From a legal point of view, the IEP needs to be approved by the parents before it can be launched by the school.

- Student (if appropriate): The child has to be included in the IEP team once they turn 16 years of age, but they can participate even earlier if this is deemed appropriate by the rest of the team. The student has the right to self-advocate for their education and to take an active part in setting up a transition plan. In many cases, they can provide valuable inputs into their own learning challenges as well as preferences to make the IEP better tailored to their specific situation.

- Translator (if needed): The school is obliged to provide a translator if one is needed to ensure smooth communications among the IEP team members. The need for a translator needs to be established in advance so that the school can make the necessary arrangements.

In addition to the obligatory members, an IEP team can include a few optional experts, such as:

- Related service provider(s): Speech therapists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and other related service providers might need to be added to the IEP team, depending on the specific disability of the child and its requirements.

- Behavioral specialist: A behavioral specialist might need to be involved in the creation of the IEP if the child exhibits certain behavioral issues that are obstructing the education process.

- Assistive technology specialist: A specialist in assistive technology has to participate in the development of the IEP in cases when specialized technology is needed to support the student in their special education plan.

- Private tutor(s): The team might include private tutors who work with the child outside the general education classroom so that they are assigned roles in the IEP and get a good understanding of the student’s needs and how they can address them in tutoring sessions.

- Advocate(s): Parents can bring advocates to the IEP meeting if they believe that they can contribute to the process. Schools, however, are not obliged to provide parent advocates.

- Friend(s): Parents and the student can choose to involve friends in the IEP process for emotional support, logistical assistance, and precious contributions if they are closely connected to the child and the family.

While it is crucial to include all required experts to develop an all-inclusive Individualized Education Program, schools should be careful to keep the size of the IEP team at a manageable level to ensure that actual results can be produced during the meetings. In case the team gets unnecessarily large, this can lead to logistical problems (finding it difficult to identify a time and place that suits everyone’s schedule) and to issues with reaching a consensus on what the most appropriate IEP is.

Types of IEP Meetings

Regular meetings of the IEP team are an indispensable part of the special education process. It is the responsibility of the school to organize meetings at least once a year to discuss, review, evaluate, and continuously improve the IEP.

Following are the types of meetings that the IEP team must have:

- Initial IEP meeting: The school needs to organize an initial meeting of the IEP team within 30 days of establishing a child’s eligibility for a child with a disability and access to special education. This meeting is crucially important as all stakeholders sit together for the first time to discuss the student’s needs and develop the first IEP that establishes the grounds for the child’s special education plan.

- Annual IEP meetings: Schools are required to hold annual meetings to evaluate the student’s progress towards the established annual goals and on grade-level standards. This is the time to adjust the IEP and to set up goals for the upcoming year.

- Triennial IEP meetings: By law, children with IEPs need to undergo triennial evaluation after which the IEP team needs to meet to discuss the evaluation findings and how they should be reflected in the education plan.

- Parent-requested IEP meetings: Parents can ask for additional meetings at any time if they think that their child’s needs are not properly and adequately addressed by the current IEP. This is an important opportunity to discuss and accommodate for new challenges that might have emerged over time.

- Amendment IEP meetings: If any of the IEP team members considers that amendments need to be made to the existing IEP, they can request an extra meeting to go over the necessary changes.

- Emergency IEP meetings: In case of behavioral issues, the team can meet outside the regular meeting schedule to address an urgent problem and incorporate additional behavioral supports into the IEP.

In terms of logistics, Individualized Education Program meetings are organized by the school. The school has to notify all team members of the purpose of the meeting and what will be discussed. Administrators need to find a time and place that is convenient for all involved parties, especially the parents of the student as at least one parent or guardian must attend each IEP meeting. IEP meetings can be held in person, on the phone, or via videoconferencing for convenience. Necessary translators need to be provided by the school to facilitate the process.

12 Common Myths about IEPs

Special education in general and IEPs in specific are associated with many myths that frequently obstruct the process and cause unnecessary inconveniences for all stakeholders, leading to suboptimal results for children who need assistance. That’s why it is important to understand and debunk myths in order to provide full clarity over the IEP requirements, eligibility, qualifications, procedures, and benefits.

Here are the 12 most common IEP myths and the reality behind them:

Myth 1: IEPs Are Only for Children with Severe Autism or Other Severe Disabilities

Many people, including some educators and school administrators, think that special education delivered via IEPs is available only to children with severe forms of disabilities, mostly autism.

The truth of the matter is that students with a wide range of disabilities - from mild to severe - can access and benefit from an Individualized Education Program. The eligibility criteria include having one or more of 13 disabilities recognized by IDEA that negatively impact the student’s performance at school, progress towards grade-level requirements, and overall academic outcomes. The key is that an IEP is tailored to the exact needs of each child which allows for children with many different challenges to take part in the program.

Myth 2: Only a Doctor Can Refer a Child to an IEP

It is a common misunderstanding that only the child’s physician can refer them to special education. Indeed, parents, teachers, and other school professionals can all request an evaluation if they suspect the child might have a disability that prevents them from thriving academically based on their experience with and observations of the child.

Nevertheless, the child’s doctor needs to be informed of the status of the child and the specific IEP as they might need to write certain prescriptions.

Myth 3: Students with Passing Grades Do Not Qualify for an IEP

The general belief is that students who get passing grades at school do not need and do not qualify for IEPs. While grades are one of the factors that lead the evaluation process, a student does not need to be failing to enroll in special education. As long as their disability affects their school performance in a negative manner, they are eligible for an IEP to let them succeed.

Myth 4: Homeschooled Children and Students at Private Schools Do Not Qualify for IEPs

While only public schools are required to provide IEPs for students, the Child Find policy obliges school districts to offer evaluation to all children who are known or suspected to have an IDEA disability. This includes students at private schools and homeschool students as well. In case a disability is confirmed, the district has to offer that the child is transferred to a public school where an appropriate IEP can be developed and implemented free of charge for the parents.

Myth 5: Once Introduced to an IEP, a Child Will Need One Forever

Another common IEP myth is that once a child has been placed in special education, they will remain labeled as “special needs” forever and will require an IEP until the end of their high-school education.

Meanwhile, the truth is that about a third of students exit IEPs before they graduate. That’s why it is crucial to conduct periodic reevaluations and to hold regular IEP meetings to continuously monitor the condition and the progress of the child and decide on the best way forward.

Myth 6: Children with IEPs Are Educated in Separate Classrooms

One of the worst stigmas that lead to the negative image of IEP and the choice of many parents to leave their children outside special education is the notion that IEP students cannot interact, communicate, cooperate, and play effectively with schoolmates so they need to be isolated and educated in specialized classrooms.

The reality is that the majority of students with IEPs study along with their classmates, attending the same general education instruction within the same classroom. Generally speaking, children with IEPs are pulled out to resource rooms for specialized services only, depending on the requirements specified in their plan.

Having said that, students with major learning disabilities or behavioral problems might need to spend most of their time in special education classrooms for individualized instruction and support. At the same time, children with severe disabilities might need to attend specialized schools, switch to homebound schooling, or even get hospital-based instruction.

In other words, where a child is instructed, educated, and supported depends entirely on their specific disability, condition, and needs.

Myth 7: Regular Education Teachers Do Not Have to Follow IEPs

According to a common misunderstanding, general education teachers do not need to participate in special education and to take into consideration IEPs. In reality, regular teachers are a major player in the process as most IEP students get the majority of their instruction in general education classes. To provide efficient support, regular education teachers need to be involved in the IEP process (as members of the IEP team), be provided with a copy of the IEP, and apply the necessary adjustments and modifications in their work with special education students.

Myth 8: Parents Have No Say in the IEP Process

Another myth about IEP that needs to be debunked to ensure higher enrollment of students in need of special education is that parents are not involved in the process and have no say in the development of the IEP. To the contrary, the law demands that parents/guardians are members of the IEP team, attend meetings, and approve the IEP before it can be introduced by the school team.

Myth 9: IEPs Put a Major Financial Burden on the Family

Some parents refrain from referring their child for evaluation and special education because they believe that the additional cost of an Individualized Education Program is prohibitively high and they cannot afford this. This is yet another myth as the truth is that IEPs are provided by public schools totally free of charge for students and their families. Parents do not need to pay anything in case their child is recognized as a child with a disability who is eligible for an IEP.

The additional cost of IEP is covered by federal funds, state funding, district grants, and private funding. Medicaid can also reimburse costs related to medical equipment and services.

Myth 10: Parents Can Receive Financial Assistance for Children with IEPs

Another misconception is that parents of children with IEPs are eligible for financial help. While this is not the case, it is important to highlight once again that enrolling a child in special education under this program comes at no additional cost to the family. All extra expenses are covered by the school, via different funds and grants.

Myth 11: Students with an IEP Cannot Go to College

Another myth that paints a very negative image of special education in general and Individualized Education Programs in specific and that prevents many children from accessing much required services and supports is the notion that IEP students cannot enroll in higher education.

In reality, many special education students end up successfully attending colleges and universities, earning degrees from them, and building careers. Once the child turns 16 years of age, transition services are included in the IEP to prepare the student for leaving the school environment and succeeding outside school. While IEPs are not available at colleges and universities, higher education institutions have their own provisions for students with disabilities and special needs to ensure that they can get access to quality education in line with their requirements and aspirations.

Fear of not being able to attend college should not prevent parents and students from requesting an IEP if the child is struggling academically because of a known or suspected disability. For many students, an IEP can turn into the pathway they need to successfully graduate from school and enroll in higher education.

Myth 12: IEPs Are the Same as 504 Plans

The final most common myth about special education is that IEPs are the same thing as 504 plans. Indeed, there are major differences between the two special education options that are designed to address the needs of children with different disabilities, in the most appropriate manner.

It is integral for educators and school administrators to know the differences between IEPs vs 504 plans in order to guide students and parents into the right path.

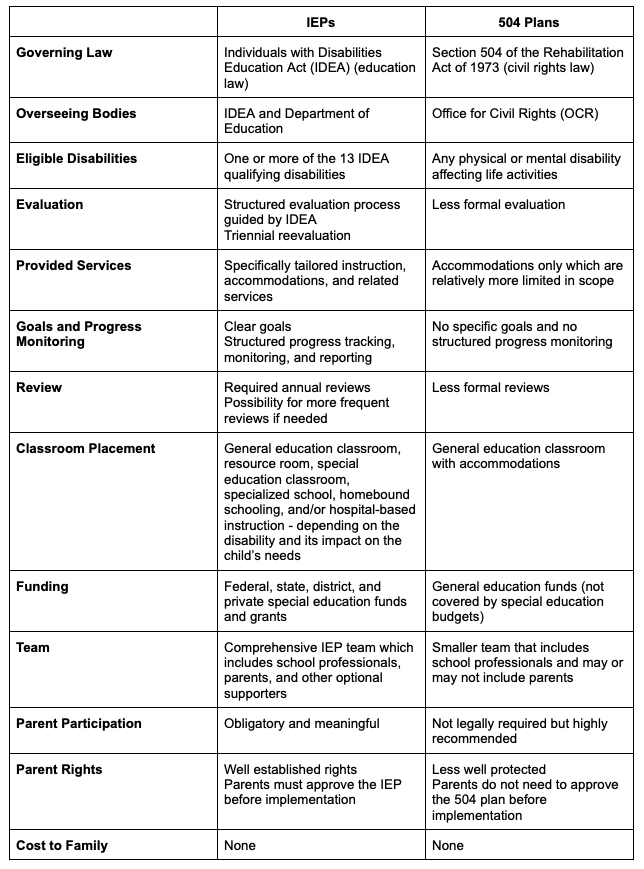

IEPs vs. 504 Plans

Individualized Education Programs are frequently confused with 504 plans and are generally believed to be the same thing. While both IEPs and 504 plans aim to address the educational needs of children with disabilities, they are two different provisions and programs that are governed in different ways and implemented in distinct manners.

Although there are some similarities between IEPs and 504 plans, there also exist major differences. Schools need to be intimately familiar with both programs in order to be able to refer children and families to the right option for their particular situation.

Following is a quick summary of the similarities and the differences between IEPs and 504 plans:

Individualized Education Programs are designed for students with specific disabilities that require special education instruction and accommodations via related services to thrive at school. The IEP process is specifically structured and requires the active participation of parents at all stages. The process is led by schools that receive special education funding from federal, state, and local sources as well as private grants to implement IEPs.

In contrast, 504 plans are meant to give students with any disability equal access to education through accommodations but do not involve specialized instruction. In other words, they are significantly more limited in scope than IEPs though more children with diverse disabilities are eligible for them. The process comprises evaluation, plan development, implementation, and monitoring, but the steps are significantly less structured and formal than with IEPs. All schools that receive government funding should offer 504 plans, but the cost is covered by general education budgets as 504 plans are not eligible for special education funding.

School administrators and educators need to understand the differences between IEPs vs 504 plans to be able to recommend students for evaluation under the right pathway for their specific disability and special education needs.

Bottom Line

IEPs are a crucial provision of the public education system to ensure that children with certain disabilities that prevent them from reaching their full academic potential get access to appropriate, quality specialized instruction, modifications, and related services with no additional cost to their family. While they are frequently confused with 504 plans, IEPs are an entirely different program that is more comprehensive and more structured to ensure the right to education of all children. The IEP process is guided by the school but integrates a number of stakeholders including general and special education teachers, school professionals, the parents, the student, and other support figures. Schools need to be well familiar with the ins and outs of the IEP process to properly address the needs of diverse student populations and provide them with the quality education they are entitled to.

Amid general teacher shortages, especially among special education teachers, Fullmind can help your district find state-certified, highly qualified K-12 special ed instructors for virtual core and supplemental instruction. Virtual staffing services are available nationwide. Get in touch to discuss the needs of your district.

For Education Leaders

Get proven strategies and expert analysis from the host of the Learning Can't Wait podcast, delivered straight to your inbox.

Let’s Work Together

We’ll review your application and get in touch!

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

%20.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)